Celebrating the History and Achievements of the American Society of Music Arrangers and Composers

by Jeannie Gayle Pool, Ph.D.

The founders of the organization, originally called ASMA (The American Society of Music Arrangers), and its subsequent Board of Directors and members have contributed greatly to the international musical heritage heard in recordings, films, television, video, and live concerts, not to mention hundreds of millions of published songs, scores, parts, and charts.

Arthur Lange (1889–1956), one of the founding members who served as President and articulate advocate and spokesman for the organization, wrote an article about the history of professional arrangers, published in January 1944. Vol. 1 No. 1 issue of ASMA’s The Score:

“It happened during the very early nineteen hundreds when the arranger was unheard of insofar as the general public was concerned. He was only known to the theatrical profession and not regarded as someone very important. He could usually be found tucked away in a remote corner of a popular music publishing house, wearing a visor, smoking a pipe, and pecking at music paper with a carefully broken-in stub pen.

“He was what was then called the "House arranger," meaning that he assumed the responsibility of doing all the arranging for that certain publishing house. In this capacity, he was required to take down melodies, make commercial piano parts, vocal orchestrations, dance orchestrations, and transpositions of vocal orchestrations for vaudeville acts. All this he would do for a weekly salary, which wasn't very much. Or, he would get paid by piecework. Taking down melodies paid twenty-five cents; piano parts, one dollar a page; vocal orchestrations, three dollars, and fifty cents; dance orchestrations, five dollars. Trans-positions paid as low as ninety cents for ‘nine and piano.’

“Of course, no arrangement was scored—orchestrations were written in the parts. But, regardless of such practice, the arranger was invariably a good musician and contributed a great deal of his own creative ability. He always supplied the Introductions, Vamps, and the much-in-demand 'Cello counter-melodies and Flute and Clarinet figurations (then called "noodles"). Such contributions were considered bought and paid for and copyrighted by the publisher, who thereby became the sole owner.

“However, in 1920 the scene suddenly changes. From the South, and from the West came the faint sounds of squealing clarinets, moaning saxophones, and strumming banjos. These sounds crescendo-ed to a fortissimo, and soon the world was dancing to a new kind of music—Jazz. And from this, the modern dance arrangements became outmoded and unusable, and dance bands were more or less forced to fake their arrangements. Of course, such practices were pooh-poohed by the old guard, who brushed it aside, saying that jazz wouldn't last. However, the up-and-coming arrangers (and I was one of them), recognized great possibilities of a new expression in dance music. Here was a chance to really do something, and the dance arranger wasted no time doing it. He became a specialist, and his contributions suddenly became valuable and important to the music industry. In fact, so important that very often the arranger's name was featured over the composer's on the printed orchestration. Dance bands wouldn't play uninteresting arrangements, and I remember many a time when I was at my wit's end trying to keep up with the parade.

“Then in 1929 came another change of scene: Radio City and Hollywood. In these surroundings the arranger again found himself confronted with many new problems. But knowing his craft and being resourceful, he soon surmounted all of them; and today he is far removed from the remote corner of a publishing house. He is now an important figure in all activities of commercial music. He is carefully chosen from a long list of capable arrangers. He is consulted on production problems, sound recording, and many other branches of the radio and motion picture industry in which only highly trained musicians can qualify.

“He works hand in hand with composer, directors, and artists; and in many instances not only conducts the orchestra himself, but composes as well. Now, what does all this sum up to? Simply this: the arranger is an indispensable and integral part of today's music industry, an industry that depends on genius to make mass production possible. Yes, dear reader, the arranger is not only a "cog in the wheel," as some may so glibly put it, but very often he is the "hub."

Lange’s description of the work of the arranger is accurate for today as it was back in 1944, although arrangers work in many more fields today, including television (beginning in the late 1940s) and video games. Unfortunately, many of the same issues facing arrangers in the 1940s face arrangers today. During the last twenty years, the use of computers and MIDI have further complicated the issues facing arrangers, orchestrators, and composers.

Early ASMA Logo

In 1938, a group of composers and arrangers writing music for movies, being dissatisfied with the lack of appreciation for their efforts, decided to band together and form an organization to promote their general interests. This group of arrangers and composers were outstanding practitioners of their art: the original officers Robert Russell Bennett, Adolph Deutsch, Hugo Friedhofer, and John Leipold, and many other distinguished Charter Members, including: Wayne Allen, Bill Anthens, Leo Arnaud, R.H. Bassett, George Bassman, Robert Russell Bennett, Frank Black, Scott Bradley, Charles Bradshaw, David Buttolph, Lucien Cailliet, John Cascales, Roy Chamberlain, A.H. Cokayne, Sidney Cutner, Murray Cutter, Adolph Deutsch, Jos. S. Dubin, Ted Duncan, Charles Eggert, Leo Erdody, Ted Fiorito, Ned Freeman, Fran Frey, Hugo Friedhofer, Emil Gerstenberger, Joe Glover, Robert Gordon, Chas. Grant, Johnny Green, Ralph H. Hallenbeck, Jr., Glenn Halley, Lou Halmy, Herman Hand, Leigh Harline, Ray Harrington, Bill Hatch, Marvin Hatley, Wally Heglin, Ray Heindorf, Charles Henderson, Frank Hubbell, Harriss Hubble, Carroll Huxley, Howard Jackson, Gordon Jenkins, Arthur Lange, Vernon Leftwich, John M. Leipold, Arthur Kay, Paul Marquardt, Charles Maxwell, James Mayfield, Paul Mertz, Charles Miller, Felix Mills, Albert Moquin, Lucien Alfred Moraweck. Spud Murphy, Joe Nussbaum, Eddy Ocnoff, George A. Osborne, George Parrish, Frank S. Perkins, Edward Plumb, E.B. Powell, Andrew Phillips, Leonid Raab, David Raksin, Max Reese, Milan Roder, Edmund Ross, Conrad Salinger, Tom Satterfield, Walter Scharf, Rudolph Schrager, Lyle E. Sharpe, Leo Shuken, Marlin Skiles, Frank Skinner, Frank M. Smith, Paul Smith, William Sodeburg, Herbert Spencer, Frederick Stark, Herbert Taylor, Robert Taylor, Dave Terry, Dave Torbett, Clifford Vaughan, Jack Virgil, Arthur Ward, John R. Weber, Clarence Wheeler, Charles Wolcott, and Harold Zweifil.

Early ASMA Logo used on issues of The Score

We have reproduced this list because many of the names are easily recognized by those familiar with the history of ASMAC. They often referred to themselves in ASMA materials as “The Hidden Men of Music.” Today’s professionals working in the music industry stand on the shoulders of these musicians. Evidence of their work is found in all aspects of the arranging-orchestrating business today. Many of these men were colleagues, friends, and mentors of our current members. An examination of the Hollywood studios' music libraries reveals that many of these people created “The Hollywood Sound.” These names appear on the published charts and arrangements of the 1930s through the 1980s and the results of their creativity are the foundation of what is known worldwide as the sound of American popular music and jazz.

Despite the fact that the founding members were also composers, they decided to stress their importance as arrangers, where their rights were sadly nonexistent. At that time, there were eight major studios—each with its own thirty-five to fifty-piece staff orchestra on the payroll. One of ASMA's first goals was to also be fully employed. When they tried to get a royalty for their orchestrations, they were dismally bound for failure, a situation that still exists to this day. They concentrated on other issues, like screen credits, better working conditions, improved union scales, even parking privileges, and anything they could think of that might not be too objectionable to studio executives.

On January 13, 1938, when ASMA was formed, the original purposes were stated:

- To further the progress of our art

- To gain greater recognition of our work

- To establish a closer bond among members of our professions

- To provide opportunity for social discussion and analysis of our work

- To promote a mutual understanding with our contemporaries; and,

- To work toward the fulfillment of the co-ordinate needs of all of the members.

Robert Russell Bennett

Robert Russell Bennett was President of ASMA during four successive terms while his career in radio, stage shows, and film, required him to shuffle back and forth between New York and Los Angeles. He conducted several network programs of symphony orchestra music, including compositions of ASMA members. Vice President Adolph Deutsch, who covered for Bennett in Los Angeles during this crucial time, remembered for the ASCAP “strike” and the controversial formation of Broadcast Music, Inc. When BMI started, it employed over a hundred and thirty arrangers, copyists, and proofreaders, employing many who had not much work during the Depression. They hoped to receive royalty payments for their work but the outmoded copyright laws put a stop to it. A big issue emerged at this time related to the AFM weekly rate for radio. During a week an arranger would produce enough score pages of orchestrations to amount to four to five hundred dollars a week, computed at union scale, but the weekly rate was a mere $160. ASMA protested and got the AFM to change it. By 1940, ASMA was working closely with Spike Wallace, Joe Weber, J.W. Gillette, and Frank Pendleton of the American Federation of Musicians to secure more lucrative contracts for arrangers.

From the very beginning of ASMA, there were New York members and Los Angeles members. Some members worked in both cities and moved back and forth, based on assignments offered to them. A formal New York chapter was established in 1944 and continued to function until the 1970s. Several prominent founding ASMA members served as NY Chapter President; the address for NY ASMA remained the same for decades: 224 West 49th Street. Throughout the 1950s, NY ASMA held monthly workshops for arrangers and composers.

The Early Years

In the early years of ASMA most of its members worked in motion picture studios and were radio arrangers, but they made an effort to recruit dance arrangers into the organization in the early 1940s. At the time Arthur Lange was considered by many to be the “Dean of Arrangers.” Lange wrote "Arranging for the Modern Dance Orchestra" which was the definitive work of its day (published by Robbins Music, 1926). Later he organized the MGM music department and was the musical director for some of the earliest sound films. He is credited with developing film scoring, music recording, and editing techniques in use for decades in the industry. In 1931, he was music director at RKO, and in 1932 became a music director for 20th Century-Fox. While there he was loaned to MGM to compose and direct the music for “The Great Ziegfeld,” which received an Academy Award for Best Picture (1936). In 1938, he became a freelancer, and co-directed and arranged the music for “The Great Victor Herbert.” By 1939, he had founded Co-Art Records and in 1945 joined International Pictures. He turned to concert music composition full-time in 1947 and assumed the conductorship of the Santa Monica Symphony Orchestra. He also taught music composition at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. For two decades, Lange was essential to the core of ASMA and recruited his employees, associates, and students, to join the organization. He mentored many arrangers and helped them get established in their careers, including several subsequent ASMA Presidents and numerous Board members.

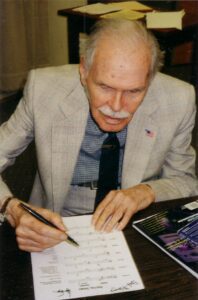

Arthur Lange

When Arthur Lange was elected to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1941, he became the first arranger to be elected to the Academy. By November 1941, ASMA boasted 106 members. The organization had monthly meetings with guest speakers—including Albert Coates, Leopold Stokowski, Edwin McArthur, Louis Gruenberg, Ernst Toch, Arnold Schoenberg, among others.

In 1941 Vernon Leftwich and Leo Arnaud organized the Beverly Hills Symphony for the purpose of playing orchestral works by ASMA members. It continued into the summer of 1942, but gas rationing during the war and the loss of the playing musicians to military service forced it to go on hiatus. In 1946 when Edward Powell was elected President of ASMA the Beverly Hills Symphony Orchestra was re-activated with players included many fine studio players and free-lance instrumentalists. During its existence it played more than 100 new works by members to large and enthusiastic audiences.

In 1942 Arthur Lange was elected ASMA President to succeed Robert Russell Bennett. Under his leadership, the difference between orchestration and arranging was defined and a new rule was inserted into Local 47’s 1943 price list declaring a definite price scale for Orchestration, but leaving the payment for any creative contribution (such as Arranging and Composition) up to the individual doing the work.

Under Lange’s leadership ASMA began publishing the newsletter, The Score, in 1943, with Rudy de Saxe as the Editor. It was a monthly publication and had a subscription of 2,500 nationally with ASMA’s membership rising to 120.

This publication elevated the status of composers, arrangers, and orchestrators working in the film industry. It contained industry news, including film credits and current projects of ASMA members. Professionally typeset and printed, it was impressive, especially considering that most music organizations mimeographed their newsletters. It ceased publication at the end of 1945 but resumed in 1950 with Joe Mullendore as the editor.

In the 1940s ASMA had a column in AFM Local 47 publication, The Overture called “Arrangers Corner” written by Arthur Lange, Charlie Maxwell, Vernon Leftwich, Adolph Deutsch, and Martin Skiles. These articles were often reprints from The Score. Several ASMA members were featured in The Overture with cover stories.

By 1944 ASMA started to grapple with antiquated copyright laws, mostly by the efforts of Edward Powell and attorney Leonard Zissu who studied the copyright law in search of a solution. They hoped to prove that the “validity of the arranger’s creative material being copyrightable”—a secondary copyright—and to determine how an arranger might derive some benefit from it. Neither a songwriter nor a publisher will give up a share of his royalty to an arranger who demands party of the royalty. He would be replaced by one who would take the job for the immediate cash involved. The AFM had no laws to protect the arrangers. Zissu and Powell had to admit that there was “no possibility of immediate justice in that direction without changing the existing copyright law.”

In July 1946, ASMA became a national organization with headquarters in Hollywood and a chapter in New York. ASMA President, Edward Powell initiated the first tentative liaison with the Screen Composers’ Association. Max Steiner, then President of the Screen Composers’ Association spoke at an ASMA meeting and declared that cooperation between the two organizations was beneficial to both, and declared ASMA a member of the Screen Composers’ Association.

Powell’s professional duties as the chief arranger and orchestrator at Twentieth-Century Fox caused him to resign as President after one year and Arthur Lange was returned to the office. ASMA had a difficult time that year because “whatever cooperation the AFM had offered to ASMA was forcibly halted by either or both of these laws”—the Lea Bill and the Taft-Hartley Law.

Herschel Gilbert, cover of March 1956 issue AFM Local 47’s “Overture”

Herschel Burke Gilbert (1918-2003) served as ASMA President for seven successive terms from 1949 until 1956. During those years, Jimmie De Michele was appointed Local 47’s representative for arrangers and orchestrators and monthly notices were published in The Overture regarding rates and contracts.

The advent of television caused ASMA to re-examine union rules and make recommendations to James Petrillo about changes to make. ASMA felt some mistakes were made in setting rates for radio and motion pictures for arrangers and that the organization needed to take extra care in looking at the situation for arrangers working in television. At issue was that arrangements originally created for motion picture were being used in television production without additional payment to the arrangers and orchestrators.

ASMA’s promotion materials declared that ASMA “voices the problems and aims of the Arranger.” ASMA was not asking for a royalty or part of the copyright (a secondary copyright) of the underlying work, but reuse and multiple use payments. At the time the same arrangement could be used for a hotel, night-club, dance band, radio broadcast, transcription, recording and motion picture all for the price of a dance arrangement which was the lowest minimum price in the field. ASMA’s position was that union scale payment must be made each and every time an arrangement or orchestration is used except for a dance orchestra, theatre orchestra or when the arrangement was specifically written for the purpose of repeated performances. “The Arrangers’ Resolution,” addressing the need for re-use payments for arrangers, orchestrators, and copyists, was accepted at the Law Committee at the 53rd Annual Convention of the AFM and forwarded to Petrillo and the Executive Board of the Federation. It called for all AFM Locals to set up basic minimum scales and working conditions for arrangers, orchestrators and copyist; that they be required to use an arranger’s stamp, dated and renewable each year for marking each sheet of music arranged with the arranger’s name, date, and the number of the local, and that re-use be prohibited without payment (except for dance orchestra or theatre orchestra arrangements specifically made for repeated use).

Lone Arranger masthead for ASMA “Off the Clef” issue.

In the 1950s, ASMA raised the issue of what do arrangers and composers have to gain by accepting the AFM as their bargaining agent. “Where does the “labor” of the composer and arranger separate itself from the “rights” he must maintain in his creations?” ASMA asked how the AFM could help composers and arrangers protect their rights? During those years ASMA continued to work closely with the Screen Composers’ Association. The protection AFM offered composers and arrangers and their music exists only for those composers and arrangers who also orchestrate or conduct. The minimum prices for the arrangers is for the orchestration only and not for any of the creative work of their arrangements. ASMA questioned why members had “to throw in for nothing” their creative work for the single price of orchestration. ASMA proposed that a system of payments to arrangers, based on royalties, be adopted, particularly for arrangements for recordings. Arrangers were (and are) paid a flat fee, while performers, publishers, and songwriters, receive royalties.

ASMA NY Chapter President Eddy Manson (later National President) described this fundamental injustice:

“Real arranging is creative work, and all music must be arranged—even rock n’ roll. We are the co-composers, for we take the melody and decide how it should be played. The ideas for hit records, the sounds, the overall design of the record, is the arranger’s responsibility. Yet, whether the record sells in the hundreds or the millions, he is paid a flat fee. Why, he doesn’t even get his name printed on the label most of time.”

“It would be interesting to learn what proportion of the background music in propaganda films distributed by our State Department is really prepared and performed by American musicians, said Russell Goudey.”

One of the founding members of ASMA, Lyle “Spud” Murphy became President in 1965 and became the longest serving President in the organization, resigning in 1977. During most of those years, he also served as a Board Member for Local 47 of the AFM and represented the interests of arrangers, orchestrators, copyists, and composers. After his ASMA presidency, he continued to serve on the ASMAC Board until his death in 2005.

The Seventies

Spud Murphy

In the 1970s, arrangers, and orchestrators continued to struggle to get a fairer contract and one fair scale for orchestrating, “with no qualification re: working from a sketch or no sketch.” ASMA wanted “to preserve the rule which says in no case can the fee for arranging be less than the scale for orchestrating. In other words, if you do both jobs, you are guaranteed equal payment for both.” Spud Murphy took the lead in negotiating these contract terms for the Record Industry. Members were encouraged to declare full scale for both arranging and orchestrating and not just for orchestrating alone, which had a huge impact on members’ pensions, benefits, and Special Payments Fund checks.

ASMA encouraged its members to ask for co-credit on the publishers’ cue sheets when one did more than orchestrate a work, for example, on the film score—which was often the case when working with an incomplete or nonexistent sketch. ASMA also suggested that its members ask for a point or two on the recording (instead of overscale payments), in addition to a royalty payment.

In 1979, the ASMA newsletter described one aspect of the problems facing arrangers.

“Whenever anyone does genuinely creative work, or adds sufficient original material to turn pre-existing material into a new work, by way of adaptation or arrangement, or any form of collaboration, that person has an inherent proprietary right; morally and ethically, he owns what he has given birth to. However, the law, in order to protect the owner of the underlying work, in the case of adaptation or arrangement or compilation, insists that permission in the form of a license be obtained before the derivative work can be protected by a copyright of its own. Also, the law states that if the arranger, adaptor or composer, for that matter, writes a work while under the employ of a second party and, in fact, the second party becomes the Author. Believe-it-or-not, this archaic, barbarous clause still exists in the copyright law.”

The only way to work around this situation is to work either as an independent contractor or be commissioned by a second party for a specific fee. ASMA encouraged its members to negotiate and to fight for some kind of ownership of one’s original creative work. ASMA carefully examined copyright law as it pertains to “derivative works” and “Work for hire” agreements to find other ways in which arrangers might seek more just terms of compensation and crediting.

In the 1970s, ASMAC once again had a regular column in The Overture called “Arranger’s Corner.” The first Golden Score Award was presented to Hugo Friedhofer in 1978 to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the organization. There were occasional lunches and annual membership meetings, which often included the Installation of Officers. The ASMA Workshops were re-invigorated in 1978 and ASMA enjoyed a close relationship during those years with the Dick Grove School of Music. If you can imagine, ASMA even had a “Ladies’ Auxiliary” in those days.

Name Change

In 1987, the name was changed to ASMAC, in recognition that most members were also practicing composers. This decision was controversial and many members opposed the change, believing that including arranger and composer in the organization’s title was redundant.

In 1988, ASMA celebrated its 50th birthday with a Golden Score dinner honoring composer John Williams. At that momentous event, held at the Plaza Hotel in Century City, Board members regaled Williams by playing his famous themes as a kazoo ensemble. That is why the event concluded with a performance of the ASMAC Chorale. For a brief time in the 1990s, ASMA resumed publication of a newsletter, which was called “Take One.”

ASMAC Chorale kazoo band at 50th anniversary Golden Score tribute to John Williams (1988)

The organization has always been committed to offering opportunities for its members to meet socially, including brunches, lunches, dinners, and cocktail receptions over the years. These occasions have been enjoyed by our members, who often work alone at home day after day, with little socializing or contact with others in the profession. This commiseration has been a key factor for some members’ personal survival in an industry that can be time-consuming, demanding, and sometimes unpleasant, with grueling deadlines and unreasonable employers.

In addition, ASMAC has had a commitment since its inception to provide its members with opportunities to improve their skills through master classes, workshops, and performances of music. Many of the performance workshops offered a “safe” environment for our members “to test out” new musical ideas and concepts with professional musicians. In the 1940s this was offered through the Beverly Hills Symphony concerts. In 1958, ASMA announced its first series of arrangers’ workshops, to focus on compositional and arranging techniques. In the 1970s and 80s, ASMAC offered dozens of such workshops yearly. During one 16-month period in 1978-79, the ASMA Composer/ Arranger’s Workshops resulted in 69 new compositions by its members.

Because much of the work of arrangers and orchestrators is so often uncredited and/or low profile, ASMAC has offered public recognition to outstanding creative talents in the profession with awards and other honors. Please see the Golden Score Award page for a list of past recipients of ASMAC’s prestigious Golden Score awards, Irwin Kostal Award, and The President’s Award.

2020 and Beyond…

During the pandemic, ASMAC hosted nearly 200 online events. As in-person events return, the organizations will include streaming, when possible. ASMAC members can re-watch nearly all those prior events online in the ASMAC video archive. Events range from score study (film, television, and big band, musical theatre), to studio tours and instrument exploration, history, and a variety of master classes (arranging, conducting, game music, film scoring, mockups among other topics).

Today membership has now grown throughout the world, and the goals and camaraderie are also continuing to expand by welcoming members who are, or have been, active in the preparation and study of music for movies, theatre, recording, television, and live performances. Through frequent seminars, master classes, workshops, and special events, ASMAC offers the public, including emerging professionals and students, opportunities to learn more about the art and craft of arranging and composition. ASMAC recognizes leaders in our field by presenting its Golden Score Award, The President's Award, and The Irwin Kostal Award.

Written by Jeannie Gayle Pool, Ph.D.

Thanks to Lance Bowling of Cambria Master Recordings and Archives for his help with this article and for memorabilia from The Arthur Lange Estate. Thanks also to Jon Burlingame and Charles Fernandez. ASMAC would greatly appreciate receiving any historic documents and photographs you might have for its archive.